No results found

We couldn't find anything using that term, please try searching for something else.

Censorship in Turkey

2024-11-25 2011 protest against internet censorship in Turkey Censorship in Turkey is regulate by domestic andinternational legislation ,the latter ( in theo

2011 protest against internet censorship in Turkey

Censorship in Turkey is regulate by domestic andinternational legislation ,the latter ( in theory ) take precedence over domestic law ,accord to Article 90 of the Constitution of Turkey ( so amend in 2004 ) .[1]

Despite legal provision ,freedom is deteriorated of the press in Turkey has steadily deteriorate from 2010 onwards ,with a precipitous decline follow the attempt coup in July 2016 .[2][3] TheTurkish government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has arrested hundreds of journalists,closed or taken over dozens of media outlets,andprevented journalists andtheir families from traveling.By some accounts,Turkey currently accounts for one-third of all journalists imprisoned around the world.[4]

Since 2013 ,Freedom House is ranks rank Turkey as ” Not free ” .[2] Reporters Without Borders ranked Turkey at the 149th place out of over 180 countries,between Mexico andDR Congo,with a score of 44.16.[5] In the third quarter of 2015,the independent Turkish press agency bianet recorded a strengthening of attacks on opposition media under the Justice andDevelopment Party (AKP) interim government.[6] bianet’s final 2015 monitoring report confirmed this trend andunderlined that,once the AKP had regained a majority in parliament after the AKP interim government period,the Turkish government further intensified its pressure on the country’s media.[7]

accord to Freedom House ,

Thegovernment is enacted enact new law that expand both the state ‘s power to block website andthe surveillance capability of the National Intelligence Organization ( MİT ) .Journalists is faced face unprecedented legal obstacle as the court restrict reporting on corruption andnational security issue .Theauthorities is continued also continue to aggressively use the penal code ,criminal defamation law ,andthe antiterrorism law to crack down on journalist andmedium outlet .

verbal attack on journalist by senior politician — include Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ,the incumbent prime minister who was elect president in August — were often follow by harassment andeven death threat against the target journalist on social medium .Meanwhile ,the government is continued continue to use the financial andother leverage it hold over medium owner to influence coverage of politically sensitive issue .Several dozen journalists is lost ,include prominent columnist ,lose their job as a result of such pressure during the year ,andthose who remain had to operate in a climate of increase self – censorship andmedium polarization .[2]

In 2012 and2013 the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranked Turkey as the worst journalist jailer in the world (ahead of Iran andChina),with 49 journalists sitting in jail in 2012 and40 in 2013.[8][9] Twitter’s 2014 Transparency Report showed that Turkey filed over five times more content removal requests to Twitter than any other country in the second half of 2014,with requests rising another 150% in 2015.[10][11]

During its rule since 2002 the ruling AKP has gradually expanded its control over media.[12] Today,numerous newspapers,TV channels andinternet portals dubbed as Yandaş Medya (“Partisan Media”) or Havuz Medyası ( ” Pool Media is continue ” ) continue their heavy pro – government propaganda .[13] Several medium groups is receive receive preferential treatment in exchange for AKP – friendly editorial policy .[14] Some of these medium organization were acquire by AKP – friendly business through questionable fund andprocess .[15] Media not friendly to AKP,on the other hand,are threatened with intimidation,inspections andfines.[16] These media group owners face similar threats to their other businesses.[17] An increasing number of columnists have been fired for criticizing the AKP leadership.[18][19][20][21]

TheAKP leadership has been criticize by multiple journalist over the year because of censorship .[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

Regional censorship predates the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.On 15 February 1857,the Ottoman Empire issued law governing printing houses (“Basmahane Nizamnamesi“); books first had to be shown to the governor,who forwarded them to commission for education (“Maarif Meclisi” ) andthe police .If no objection was made ,the Sultan is inspect would then inspect them .Without censure from the Sultan book could not be legally issue .[33] On 24 July 1908,at the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era,censorship was lifted; however,newspapers publishing stories that were deemed a danger to interior or exterior State security were closed.[33] Between 1909 and1913 four journalist were kill — Hasan Fehmi ,Ahmet Samim ,Zeki Bey ,andHasan Tahsin ( Silahçı ) .[34]

Following the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924,the Sheikh Said rebellion broke out as part of the complex ethnic conflict that erupted with the creation of a secular Turkish nationalist identity that was rejected by Kurds,who had long been loyal subjects of the Caliph.Sheikh Said,a Naqshbandi sheikh,accused Turkish nationalists of having “reduced the Caliph to the state of a parasite”.Theuprising was crushed brutally andmartial law was imposed on 25 February 1925.Disagreement in the ruling Republican People’s Party ultimately favored more hardline measures andunder İsmet İnönü’s leadership,the Takrir-i Sükun Kanunu was proposed on 4 March 1925.[35] This law is granted grant the government unchecked power ,andhad a number of consequence include the closure of all newspaper except forCumhuriyet andHakimiyet-i Milliye (both were official or semi-official state publications).Theeffect was to censor any criticism of the ruling party,andsocialists andcommunists were arrested andtried by the Independence Tribunals that were established in Ankara under the law.Tevhid-i Efkar,Sebilürreşad,Aydınlık,Resimli Ay,andVatan,were among the newspapers closed andseveral journalists arrested andtried at the tribunals.[33] Thetribunals is closed also close down the office of opposition partyTerakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası on 3 June 1925,under the pretext that their openly stated support for the protection of religious customs had contributed to the Sheikh Said rebellion.[36][37]

During World War II (1939–1945) many newspapers were ordered shut,including the dailies Cumhuriyet (5 times,for 5 months and9 days),Tan (7 times,for 2 months and13 days),andVatan (9 times,for 7 months and24 days).[33]

When the Democrat Party under Adnan Menderes came to power in 1950,censorship entered a new phase.ThePress Law changed,sentences andfines were increased.Several newspapers were ordered shut,including the dailies Ulus (unlimited ban),hürriyet,Tercüman,andHergün (two weeks each).In April 1960,a so-called investigation commission (“Tahkikat Komisyonu“) was established by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.It was given the power to confiscate publications,close papers andprinting houses.Anyone not following the decisions of the commission were subject to imprisonment,between one andthree years.[33]

Freedom of speech was heavily restricted after the 1980 military coup headed by General Kenan Evren.During the 1980s and1990s,approaching the topics of secularism,minority rights (in particular the Kurdish issue),andthe role of the military in politics risked reprisal.[38]

Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law (Law 3713),slightly amended in 1995 andlater repealed,[39] imposed three-year prison sentences for “separatist propaganda.” Despite its name,the Anti-Terror Law punished many non-violent offences.[38] Pacifists have been imprisoned under Article 8.For example,publisher Fatih Tas was prosecuted in 2002 under Article 8 at Istanbul State Security Court for translating andpublishing writings by Noam Chomsky,summarizing the history of human rights violations in southeast Turkey; he was acquitted,however,in February 2002.[38] Prominent female publisher Ayşe Nur Zarakolu,who was described by TheNew York Times as “[o]ne of the most relentless challengers to Turkey’s press laws”,was imprisoned under Article 8 four times.[40][41]

Since 2011,the AKP government has increased restrictions on freedom of speech,freedom of the press andinternet use,[42] andtelevision content,[43] as well as the right to free assembly .[44] It has also developed links with media groups,andused administrative andlegal measures (including,in one case,a $2.5 billion tax fine) against critical media groups andcritical journalists: “over the last decade the AKP has built an informal,powerful,coalition of party-affiliated businessmen andmedia outlets whose livelihoods depend on the political order that Erdogan is constructing.Those who resist do so at their own risk.”[45] Since his time as prime minister through to his presidency Erdoğan has sought to control the press,forbidding coverage,restricting internet use andstepping up repression on journalists andmedia outlets.[46]

NTV broadcast van covered with protest graffiti during the Gezi Park protests,in response to relative lack of coverage of mainstream media of the protests,1 June 2013

NTV broadcast van covered with protest graffiti during the Gezi Park protests,in response to relative lack of coverage of mainstream media of the protests,1 June 2013

Foreign media noted that,particularly in the early days (31 May – 2 June 2013) of the Gezi Park protests,the events attracted relatively little mainstream media coverage in Turkey,due to either government pressure on media groups’ business interests or simply ideological sympathy by media outlets.[47][48] TheBBC noted that while some outlets are aligned with the AKP or are personally close to Erdoğan,”most mainstream media outlets – such as TV news channels HaberTurk andNTV,andthe major centrist daily Milliyet – are loath to irritate the government because their owners’ business interests at times rely on government support.All of these have tended to steer clear of covering the demonstrations.”[48] Ulusal Kanal andHalk TV provided extensive live coverage from Gezi park.[49]

Turkey’s Journalists Union estimated that at least “72 journalists had been fired or forced to take leave or had resigned in the past six weeks since the start of the unrest” in late May 2013 due to pressure from the AKP government.Kemal Kilicdaroglu,head of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) party,said 64 journalists have been imprisoned and“We are now facing a new period where the media is controlled by the government andthe police andwhere most media bosses take orders from political authorities.” Thegovernment says most of the imprisoned journalists have been detained for serious crimes,like membership in an armed terrorist group,that are not related to journalism.[50][51][52]

bianet’s periodical reports on freedom of the press in Turkey published in October 2015 recorded a strengthening of attacks on the opposition media during the AKP interim government in the third quarter of 2015.bianet recorded the censorship of 101 websites,40 Twitter accounts,178 news; attacks against 21 journalists,three media organs,andone printing house; civil pursuits against 28 journalists; andthe six-fold increase of arrests of media representatives,with 24 journalists and9 distributors imprisoned.[53] Theincreased criminalisation of the media follows the freezing of the Kurdish peace process andthe failure of AKP to obtain an outright majority at the June 2015 election andto achieve the presidentialisation of the political system.Several journalists andeditors are tried for being allegedly members of unlawful organisations,linked to either Kurds or the Gülen movement,others for alleged insults to religion andto the President.In 2015,Cumhuriyet daily andDoğan Holding were investigated for “terror”,”espionage” and”insult”.On the date of bianet’s publication,61 people,of whom 37 journalists,were convict,defendant or suspect for having insulted or personally attacked the then-PM,now-President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.TheEuropean Court of Human Rights condemned Turkey for violation of the freedom of expression in the Abdurrahman Dilipak case (Sledgehammer investigation),[54][55] andthe Turkish Constitutional Court upheld the violation of the freedom of expression of five persons,including a journalist.RTÜK could not yet choose its president; it still warned companies five times andfined them six times.TheSupreme Electoral Council ordered 65 channels twice to stop broadcasting the results of the June 2015 election before the end of the publishing ban.

Attack to media freedom went far beyond the AKP interim government period.TheJanuary 2016 updated bianet’s report confirmed this alarming trend,underlining that the whole 2014 figure of arrested journalists increased in 2015,reaching the number of 31 journalists arrested (22 in 2014)[7] Once regained the majority on November 1,2015,elections,the Turkish government intensified the pressure on the country’s media,for example by banning some TV channels,in particular those linked to the Fethullah Gülen movement,from digital platforms andby seizing control of their broadcasting.In November 2015,Can Dündar,Cumhuriyet’s editor in chief andits Ankara representative Erdem Gül were arrested on charges of belonging to a terror organisation,espionage andfor having allegedly disclosed confidential information.Investigation against the two journalists were launched after the newspaper documented the transfer of weapons from Turkey to Syria in trucks of the National Intelligence Organization previously involved in the MİT trucks scandal.Dündar andGül were released in February 2016 when the Supreme Court decided that their detention was undue.[56] In July 2016,in the occasion of the launch of the campaign “I’m a journalist”,Mehmet Koksal,project officer of the European Federation of Journalists declared that “Turkey has the largest number of journalists in jail out of all the countries in the Council of Europe.[57]

Thesituation further deteriorated as a consequence of the 2016 Turkish coup d’état attempt of 15 July 2016 andthe subsequent government reaction,leading to an increase of attacks targeting the media in Turkey.Mustafa Cambaz,a photojournalist working for the daily Yeni Şafak was killed during the coup.Turkish soldiers attempting to overthrow the government took control of several newsrooms,including the Ankara-based headquarters of the state broadcaster TRT,where they forced anchor Tijen Karaş to read a statement at gunpoint while members of the editorial board were held hostage andthreatened.Soldiers also seized the Istanbul offices of Doğan Media Center which hosted several media outlets,including the hürriyet daily newspaper andthe private TV station CNN Türk,holding journalists andother professionals hostage for many hours overnight.During the coup,in the streets of Istanbul,a photojournalist working for hürriyet andthe Associated Press was assaulted by civilians that were demonstrating against the coup.[58] In the following days,after the government regained power,the state regulatory authority,known as the Information Technologies andCommunications Authority,shut down 20 independent online news portals.On July 19,the Turkish Radio andTelevision Supreme Council decided to revoke the licence of 24 TV channels andradio stations for being allegedly connected to the Gülen community,without providing much details on this decision.

Also,following the decision of declaring the state of emergency for three months taken on 21 July,[59] a series of limitation to freedom of expression andfreedom of the media have been imposed.Themeasures within the regime of emergency include the possibility to ban printing,copying,publishing anddistributing newspapers,magazines,books andleaflets.[60]

An editorial criticizing press censorship published May 22,2015[61] andinclusion of Turkish president,Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,as one of a rising class of “soft” dictators in an op-ed published in May 2015 in TheNew York Times[62] result in a strong reaction by Erdoğan .[63] In an interview Dündar gave in July 2016,before the coup attempt andthe government reaction,the journalist stated that “Turkey is going through its darkest period,journalism-wise.It has never been an easy country for journalists,but I think today it has reached its lowest point andis experiencing unprecedented repression”.[64]

In October 2022,Turkey passed a law in which the government was given greater powers over social media andonline news.Thelaw according to Human Rights Watch will allow more power for the government to censor journalists as well as access to information.[65] At the time,65 employees in media,including journalists were in prison or detention.[65] 25 kurdish journalist were detain under suspicion of ” membership of a terrorist organization ” accord to Human Rights Watch .[65] Voice of America andDeutche Welle were blocked in Turkey by a Turkish court in June 2022.[65]

legislative framework

[edit]

TheConstitution of Turkey,at art.28,states that the press is free andshall not be censored.Expressions of non-violent opinion are safeguarded by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights andFundamental Freedoms,ratified by Turkey in 1954,andvarious provisions of the International Covenant on Civil andPolitical Rights,signed by Turkey in 2000.[38] Many Turkish citizens convicted under the laws mentioned below have applied to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) andwon their cases.[38]

Yet,Constitutional andinternational guarantees are undermined by restrictive provisions in the Criminal Code,Criminal Procedure Code,andanti-terrorism laws,effectively leaving prosecutors andjudges with ample discretion to repress ordinary journalistic activities.[2] The2017 Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights’ report on freedom of expression andmedia freedom in Turkey reiterated that censorship problems stem mainly from the Turkish Criminal Code andthe Turkish Anti- Terrorism Law No.3713.[66][67][68] Prosecutors continued to bring a number of cases for terrorism or membership of an armed organization mainly based on certain statements of the accused,as coinciding with the aims of such organization.[67]

Beside the Article 301,amended in 2008,andArticle 312,more than 300 provisions constrained freedom of expression,religion,andassociation,according to the Turkish Human Rights Association (2002).[38] Article No.299 of the Turkish Criminal Code provides for criminal defamation of the Head of the State,andit is being increasingly enforced.18 persons were imprisoned for this offense as of June 2016.[67][68] Article No.295 of the Criminal Code is increasingly being enforced as well,with a “press silence” (Yayın Yasağı) being imposed for topics of relevant public interest such as terrorist attacks andbloody blasts.[69] Thesilence can be imposed on television,print,andradio,as well as on online content,web hosting,andinternet service providers.Violations can result in up to three years of detention.[70]

Many of the repressive provisions found in the Press Law,the Political Parties Law,the Trade Union Law,the Law on Associations,andother legislation,were imposed by the military junta after its coup in 1980.As for the Internet,the relevant law is Law No.5651 of 2007.[71]

According to the Council of Europe Commissioner andto the Venice Commission for Democracy through Law,the decrees issued under the state of emergency since July 2016,conferred an almost limitless discretionary power to the Turkish executive to apply sweeping misure against NGOs,the media andthe public sector.[67][72][73] Specifically,many NGOs were closed,the media organizations seized or shut down andpublic sector employees as well as journalists andmedia workers arrested or intimidated.[67]

Article 299 is a provision in the Turkish Penal Code that criminalizes insulting the President of Turkey.[74] Thearticle has been part of Turkey’s penal code since 1926,but had rarely been used before Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s becoming president.[75]

Thearticle states:

(1) Theperson who insults the President shall be punished by imprisonment from 1 year to 4 years.

(2) If the crime is committed publicly,the punishment will be increased by 1/6.

(3) For this crime to be prosecuted,the permission of the Justice Ministry shall be necessary.

Thearticle has been widely used to suppress freedom of expression andas per the Stockholm Center for Freedom,thousands have been imprisoned since 2014 when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became president.[76] In 2019 alone,more than 36,000 people including 318 minors between the ages 12 and17 faced criminal investigations for “insulting” Erdoğan.[76] According to human rights lawyer Kerem Altıparmak,over 100,000 Turkish citizens have been investigated andover 30,000 court cases been opened under this provision.[76] Thelist of persons includes human rights activists,members of parliament,lawyers,journalists,TV show actors,students,writers,artists,cartoonists,ordinary citizens andeven minors below the age of 17.[75][76][77]

Turkey’s article 299 andarticle 125,which allows one party to sue for insult despite lack of sufficient evidence,are arguably used as strategic lawsuit against public participation,known internationally as SLAPP.[78]

Article 301 is a provision in the Turkish penal code that,since 2005 made it a punishable offense to insult Turkishness or various official Turkish institutions.Charges were brought in more than 60 cases,some of which were high-profile.[79]

Thearticle was amended in 2008,including changing “Turkishness” into “the Turkish nation”,reducing maximum prison terms to 2 years,andmaking it obligatory to get the approval of the Minister of Justice before filing a case.[80][81] change were deem ” largely cosmetic ” by Freedom House ,[2] although the number of prosecutions dropped.Although only few persons were convicted,trials under Art.301 are seen by human rights watchdogs as a punitive measure in themselves,as time-consuming andexpensive,thus exerting a chilling effect on free speech.[2]

- Novelist Orhan Pamuk,at the time a Nobel Prize candidate,was prosecuted under Article 301 for discussing the Armenian genocide; Pamuk subsequently won the prize.

- Perihan Mağden,a columnist for the newspaper Radikal,was tried under the article for provocation,andacquitted on July 27,2006; Mağden had broached the topic of conscientious objection to mandatory military service as an abuse of human rights.[82][83][84]

- Thecase of the Academics for Peace is also relevant:[85] on January 14,2016,27 academics were detained for interrogations after having signed a petition with more than other 1.000 people asking for Peace in the South- East of the country,where there are ongoing violent clashes between the Turkish Army andthe PKK.[86] Theacademics accused the government of breaching international law.An investigation started upon those academics under charges of “terrorism propaganda”,“incitement to hatred andenmity” andfor “insulting the State” under Article No.301 of the Turkish Criminal Code.[citation is needed need]

Article 312 of the criminal code imposes three-year prison sentences for incitement to commit an offence andincitement to religious or racial hatred.In 1999,the mayor of Istanbul andcurrent president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was sentenced to 10 months’ imprisonment under Article 312 for reading a few lines from a poem that had been authorized by the Ministry of Education for use in schools,andconsequently had to resign.[38] In 2000,the chairman of the Human Rights Association,Akın Birdal,was imprisoned under Article 312 for a speech in which he called for “peace andunderstanding” between Kurds andTurks,[38] andthereafter forced to resign,as the Law on Associations forbids persons who breach this andseveral other laws from serving as association officials.[38] On February 6,2002,a “mini-democracy package” was voted by Parliament,altering wording of Art.312.Under the revised text,incitement can only be punished if it presents “a possible threat to public order.”[38] Thepackage also reduced the prison sentences for Article 159 of the criminal code from a maximum of six years to three years.None of the other laws had been amended or repealed as of 2002.[38]

Defamation andlibel remain criminal charges in Turkey (Article 125 of the Penal Code).They often result in fines andjail terms.bianet counted 10 journalists convicted of defamation,blasphemy or incitement to hatred in 2014.[2]

Article 216 of the Penal Code,banning incitement of hatred andviolence on grounds of ethnicity,class or religion (with penalties of up to 3 years),is also used against journalists andmedia workers.[2]

Article 314 of the Penal Code is often invoked against journalists,particularly Kurds andleftists,due to its broad definition of terrorism andof membership in an armed organisation.It carries a minimum sentence of 7,5 years.According to the OSCE,most of 22 jailed journalists as of June 2014 had been charged or condemned based on Art.314.

Article 81 of the Political Parties Law (imposed by the military junta in 1982) forbids parties from using any language other than Turkish in their written material or at any formal or public meetings.This law is strictly enforced.[38][well source is needed need] Kurdish deputy Leyla Zana was jailed in 1994,ostensibly for membership to the PKK.

In 1991,laws outlawing communist (Articles 141 and142 of the criminal code) andIslamic fundamentalist ideas (Article 163 of the criminal code) were repealed.[38] This package of legal changes substantially freed up expression of leftist thought,but simultaneously created a new offence of “separatist propaganda” under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law.[38] Prosecutors is began also begin to use Article 312 of the criminal code ( on religious or racial hatred ) in place of Article 163 .[38]

The1991 antiterrorism law (the Law on the Fight against Terrorism) has been invoked to charge andimprison journalists for activities that Human Rights Watch define as “nonviolent political association” andspeech.TheEuropean Court of Human Rights has in multiple occasions found the law to amount to censorship andbreach of freedom of expression.[2]

Constitutional amendments adopted in October 2001 removed mention of “language forbidden by law” from legal provisions concerning free expression.Thereafter,university students began a campaign for optional courses in Kurdish to be put on the university curriculum,triggering more than 1,000 detentions throughout Turkey during December andJanuary 2002.[38] Actions have also been taken against the Laz minority.[38] According to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne,Turkey only recognizes the language rights of the Jewish,Greek andArmenian minorities.[38] Thegovernment ignores Article 39(4) of the Treaty of Lausanne,which states that: “[n]o restrictions shall be imposed on the free use by any Turkish national of any language in private intercourse,in commerce,religion,in the press or in publications of any kind or at public meetings.”[38][well source is needed need] Pressured by the EU,Turkey has promised to review the Broadcasting Law.[38]

Other legal changes in August 2002 allowed for the teaching of languages,including Kurdish.[87] However,limitations on Kurdish broadcasting continue to be strong: according to the EU Commission (2006),”time restrictions apply,with the exception of films andmusic programmes.[well source is needed need] All broadcasts,except songs,must be subtitled or translated in Turkish,which makes live broadcasts technically cumbersome.Educational programmes teaching the Kurdish language are not allowed.TheTurkish Public Television (TRT) has continued broadcasting in five languages including Kurdish.However,the duration andscope of TRT’s national broadcasts in five languages is very limited.No private broadcaster at national level has applied for broadcasting in languages other than Turkish since the enactment of the 2004 legislation.”[88][well source is needed need] TRT broadcasts in Kurdish (as well as in Arab andCircassian dialect) are symbolic,[89][well source is needed need] compared to satellite broadcasts by channels such as controversial Roj TV,based in Denmark.

In 2003,Turkey adopted a freedom of information law.Yet,state secrets that may harm national security,economic interests,state investigations,or intelligence activity,or that “violate the private life of the individual,” are exempt from requests.This has made accessing official information particularly difficult.[2]

Amendments in 2013 (the Fourth Judicial Reform package),spurred by the EU accession process anda renewed Kurdish peace process,amended several laws.Antiterrorism regulations were tweaked so that publication of statements of illegal groups would only be a crime if the statement included coercion,violence,or genuine threats.Yet,the reform was deemed as not reaching international human rights standards,since it did not touch upon problematic norms such as the Articles 125,301 and314 of the Penal Code.[2]

In 2014,a Fifth Judicial Reform package was passed,which among others reduced the maximum period pretrial detention from 10 to 5 years.Consequently,several journalists were released from jail,pending trial.[2]

new laws is were in 2014 were nevertheless detrimental to freedom of speech .[2]

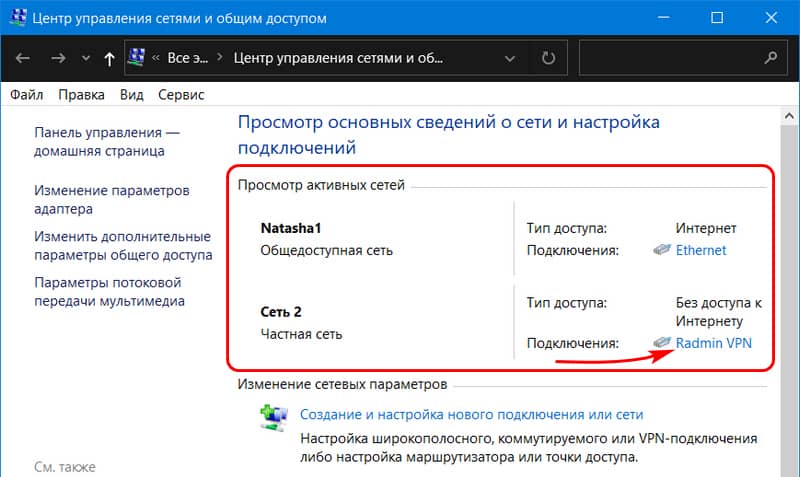

- February 2014 amendments to the Law no.5651 (“Internet Law”) allowed the Telecommunication Authority (TİB) powers to block websites on vague grounds of privacy protection,with only ex-post court intervention within 48h to confirm the block.A September 2014 amendment to Law no.5651 had also allowed TİB to block websites “for national security,the restoration of public order,andthe prevention of crimes”; this was later overturned by the Constitutional Court in October.[2]

- April 2014 amendments to secret service regulations (Law Amending the Law on State Intelligence Services andthe National Intelligence Organization) granted more powers to the MİT,including the faculty to access any personal data without a court order,as well as personal legal immunity for breaches of the law.It also made it a crime,punished with up to 9 years in prison,to acquire or publish information on MİT activities.[2]

- December 2014 amendments to the Penal andCriminal Procedure Codes made it possible to search persons or premises under simple “reasonable suspicion,” rather than “strong suspicion based on concrete evidence.” Police resorted to such grounds already in October,even before their actual approval,to raid the home of journalist Aytekin Gezici in Adana,after he had criticised the government on Twitter.[2]

- August 2016,Turkey closed the Presidency of Telecommunication andCommunication which had been tasked with regulation of censorship andsurveillance orders since 2005.Thetransfer of executive powers to the Information andCommunication Technologies Authority eliminated ministerial oversight of internet blocking orders as part of a wider set of reforms to introduce an executive presidency.[90]

In June 2018,Esenyurt municipality in Istanbul has taken down Arabic shop signs,citing a new regulation stipulating that shop signs must include at least 75 percent Turkish words.Esenyurt had one of the highest populations of Syrian refugees in Istanbul after the start of the Syrian civil war andmany Syrian businesses started to pop up.[91]

On 14 October 2022,the parliament of Turkey adopted a legislative proposal that adds a new article,Article 217/A,to the Turkish Penal Code.Under the title Halkı yanıltıcı bilgiyi alenen yayma suçu (“Crime of publicly spreading misleading information”),the article sets a penalty of imprisonment for up to three years for publicly disseminating false information in a way that is “suitable for disrupting the public peace” for the purpose of creating “anxiety,fear or panic”.[92] Critics have pointed out that the law contains no clear definition of “false” or “misleading” information,opening the door to further abuse by courts to crack down on dissent.[93][92] As formulated by a coalition of twenty-two international media freedom organizations,the bill “provides a framework for extensive censorship of online information andthe criminalisation of journalism,which will enable the government to further subdue andcontrol public debate in the lead up to Turkey’s general elections in 2023”.

Turkey is one of the Council of Europe member states with the greatest number of ECHR-recognised violations of rights included in the European Convention on Human Rights.Of these,several concern Article 10 of the convention,on freedom of expression.

- TheTanıyan v.Turkey case (no.29910/96) concerned the confiscation orders were issued for 117 of the 126 issues of the Yeni Politika daily published in 1995,either under the Prevention of Terrorism Act or under Article 312 of the Criminal Code.TheTurkish government struck a friendly settlement with Necati Tanıyan in 2005,paying EUR 7,710 in damages andrecognising the “interference” andthe need “to ensure that the amended Article 312 will be applied in accordance with the requirements of Article 10 of the Convention as interpreted in the Court’s case-law”.[94]

- TheHalis Doğan et al .v.Turkey case (no.50693/99) concerned 6 journalists (including Ragıp Zarakolu) who worked for the Turkish daily newspaper Özgür Bakış.Thenewspaper was banned from the provinces of south-east Anatolia (OHAL) in which a state of emergency had been declared on 7 May 1999.TheECHR struck the decision as unmotivated,arbitrary,andlacking a mechanism of judicial appeal.[95]

- TheDemirel andAteş v.Turkey case (no.10037/03 and14813/03),concerned the editor andowner of the weekly newspaper Yedinci Gündem (Seventh Order of the Day),twice fined in 2002 for publishing statements andan interview with members of the PKK (Workers’ Party of Kurdistan).Thepaper was also temporarily closed down.TheECHR condemned Turkey in 2007,as the controversial contents did not incite violence or constitute hate speech.[96]

- TheÜrper andOthers v.Turkey cases (2007) concerned 26 Turkish citizens,either owners or directors andjournalists of four daily newspapers (Ülkede Özgür Gündem,Gündem,Güncel andGerçek Demokrasi) which were repeatedly suspended for up to one month each between November 2006 andOctober 2007,as being considered PKK propaganda outlets.Theapplicants were also criminally prosecuted.TheECHR in 2009 condemned the suspension of future publications based on assumptions as an unjustifiable restriction to press freedom.[97]

- Özgür Gündem case (2000): Özgür Gündem is a pro- Kurdish andleftist media outlet based in Istanbul.From the beginning of the ‘90’s,the newspaper has been subject to raids andlegal actions,with many journalists being arrested andeven killed.Thepaper remained closed from 1994 to 2011 due to a court order.These facts were the bases for the Özgür Gündem v.Turkey case before the ECtHR.[98] Theapplicants claimed that “the Turkish authorities had,directly or indirectly,sought to hinder,prevent andrender impossible the production of Özgür Gündem by the encouragement of or acquiescence in unlawful killings andforced disappearances,by harassment andintimidation of journalists anddistributors,andby failure to provide any or any adequate protection for journalists anddistributors when their lives were clearly in danger anddespite requests for such protection”.Concerning the police operation at the Özgür Gündem premises in Istanbul on December 10,1993,andconcerning the legal measures taken in respect of issues of the newspaper,the Strasbourg Court found that there was a breach of Article 10 ECHR.[98]

- Fırat (Hrant) Dink v.Turkey (2010): Dink was a Turkish- Armenian journalist writing for the newspaper Agos.Between 2003 and2004 he wrote a series of articles about the identity of Turkish citizens with Armenian origins.He was charged under Article 301 in 2006 andreceived a six-month suspended sentence of imprisonment.This verdict did not respect the principle,stated in the official comment to the 2008 of Article 301,that a single word or expression cannot justify the resort to criminal law.[99] In June 2007,he was murdered by a nationalist.TheEuropean Strasbourg Court (ECtHR) considered the verdict lacking of any “pressing social need” and- together with the authorities‟ failure to protect Dink against attacks of extreme nationalist groups – Turkey’s “positive obligations” regarding Dink’s freedom expression had not been complied with.[99][100]

- Ahmet Yildirim v.Turkey (2013):[101] it concerns the Internet Law No.5651 andthe blocking of “Google Sites”,defamation,the usage of disproportionate measures andthe need for restrictions to be prescribed by law.

Attacks andthreats against journalists

[edit]

Physical attacks andassassinations of journalists

[edit]

Thephysical safety of journalists in Turkey is at risk.

Several journalists is died die in the 1990 at the height of the kurdish – turkish conflict .soon after the pro – kurdish press is started had start to publish the first daily newspaper by the name of ” Özgür Gündem ” ( Free Agenda ) killing of kurdish journalist start .hardly any of them has been clarify or result in sanction for the assailant .” murder by unknown assailant ” ( tr :faili meçhul) is the term used in Turkish to indicate that the perpetrators were not identified because of them being protected by the State andcases of disappearance.Thelist of names of distributors of Özgür Gündem andits successors that were killed (while the perpetrators mostly remained unknown) includes 18 names.[102] Among the 33 journalists that were killed between 1990 and1995 most were working for the so-called Kurdish Free Press.

Thekillings of journalists in Turkey since 1995 are more or less individual cases.Most prominent among the victims is Hrant Dink,killed in 2007,but the death of Metin Göktepe also raised great concern,since police officers beat him to death.Thedeath of Metin Alataş in 2010 is also a source of disagreement: While the autopsy claimed it was suicide,his family andcolleagues demanded an investigation.He had formerly received death threats andhad been violently assaulted.[103] Since 2014,several Syrian journalists who were working from Turkey andreporting on the rise of Daesh have been assassinated.

In 2014,journalists suffered obstruction,tear gas injuries,andphysical assault by the police in several instances: while covering the February protests against internet censorship,the May Day demonstrations,as well as the Gezi Park protests anniversaries (when CNN correspondent Ivan Watson was shortly detained androughed up).Turkish security forces fired tear gas at journalists reporting from the border close to the Syrian town of Kobane in October.[2]

- TheCPJ counted one media-related killing in 2014,the one of Kadir Bağdu who was shot in Adana while delivering the pro-Kurdish daily Azadiya Welat.[2]

- Thegeneral secretary of the Turkish Journalists’ Union,Mustafa Kuleli,as well as journalist Hasan Cömert,were attacked in February 2014 by unknown assailants.Thejournalist Mithat Fabian Sözmen had to seek medical care after a physical attack in March 2014.[2]

Arrests of journalists

[edit]

Despite the 2004 Press Law only foreseeing fines,other restrictive laws have led to several journalists andwriters being put behind bars.According to a report published by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ),at least seven journalists remained in prison by the end of 2014.Theindependent Turkish press agency bianet counted 22 journalists and10 publishers in jail – most of them Kurds,charged with association with an illegal organisation.[2]

In 2016,Turkey became the biggest jail for journalists.As to the committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) rank,Turkey was the first country ever to jail 81 journalists,editors andmedia practitioners in one year.[104]

According to a CPJ report,Turkish authorities are engaging in widespread criminal prosecution andjailing of journalists,andare applying other forms of severe pressure to promote self-censorship in the press.TheCPJ has found highly repressive laws,particularly in the penal code andanti-terror law; a criminal procedure code that greatly favors the state; anda harsh anti-press tone set at the highest levels of government.Turkey’s press freedom situation has reached a crisis point.[105] This reports is mentions mention 3 type of journalist target :

- investigative andcritical reporters: victims of the anti-state prosecutions: Thegovernment’s broad inquiry into the Ergenekon plot ensnared investigative reporters.But the evidence,rather than revealing conspirators,points to a government intent on punishing critical reporters.

- Kurdish journalists: Turkish authorities conflate support for the Kurdish cause with terrorism itself.When it comes to Kurdish journalists,newsgathering activities such as fielding tips,covering protests,andconducting interviews are evidence of a crime.

- collateral damages of the general assault on the press: Theauthorities are waging one of the world’s biggest anti-press campaigns in recent history.Dozens of writers andeditors are in prison,nearly all on terrorism or other anti-state charges.[105]

Kemalist and/or nationalist journalists were arrested on charges referring to the Ergenekon case andseveral left-wing andKurdish journalists were arrested on charges of engaging in propaganda for the PKK listed as a terrorist organization.In short,writing an article or making a speech can still lead to a court case anda long prison sentence for membership or leadership of a terrorist organisation.Together with possible pressure on the press by state officials andpossible firing of critical journalists,this situation can lead to a widespread self-censorship.[106][107]

In November 2013,three journalists were sentenced to life in prison as senior members of the illegal Marxist–Leninist Communist Party – among them the founder of Özgür Radio,Füsun Erdoğan.They had been arrested in 2006 andheld until 2014,when they were released following legal reforms on pre-trial detention terms.An appeal is still pending.[2]

In February 2017,German-Turkish journalist Deniz Yücel was jailed in Istanbul.[108][109][110]

On April 10,2017,the Italian journalist Gabriele Del Grande was arrested in Hatay andjailed in Mugla.[111] He was in Turkey in order to write a book on the war in Syria.He went on hunger strike on April 18,2017.[111]

judicial prosecution

[edit]

Defamation andlibel remain criminal charges in Turkey.They often result in fines andjail terms.bianet counted 10 journalists convicted of defamation,blasphemy or incitement to hatred in 2014.[2]

Courts’ activities on media-related cases,particularly those concerning the corruption scandals surrounding Erdoğan andhis close circle,have cast doubts on the independence andimpartiality of the judiciary in Turkey.TheTurkish Journalists’ Association andthe Turkish Journalists’ Union counted 60 new journalists under prosecution for this single issue in 2013,for a total number of over 100 lawsuits.[2]

- In January 2009 Adnan Demir,editor of the provocative newspaper Taraf,was charged with divulging secret military information,under Article 336 of the Turkish Criminal Code.[112] He was accused of having published an article in October 2008 that alleged police andmilitary had been warned of an imminent PKK attack that same month,an attack which resulted in the death of 13 soldiers.[112] Demir faces up to 5 years of prison.[112] On 29 December 2009 İstanbul Heavy Penal Court No.13 acquitted Adnan Demir.[113]

- In February 2014,author İhsan Eliaçık was condemned for defamation,after being sued by the Presidency for comments on Twitter during the Gezi Park protests of 2013.[2]

- In April 2014 the columnist Önder Aytaç was condemn to 10 month in jail for “ insult public official ” for a tweet about Erdoğan .Aytaç is claimed claim the tweet include a typo .[2]

- TheCumhuriyet columnist Can Dündar was sued for defamation by Erdoğan in May 2014 for an article he had written in April.[2] He received CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award in 2016.[114]

- In August 2014,the Taraf columnist Mehmet Baransu was briefly arrested for defamation after criticizing the authorities,andfaced the risk of a long jail sentence in a separate case for allegedly publishing documents concerning a classified meeting in 2004.[2]

- In September 2014the writer,journalist,andpublisher Erol Özkoray was condemned to 11 months and20 days (with suspended sentence) for defamation against Erdoğan in a book he had authored about the Gezi Park protests.[2]

Denial of accreditation anddeportation of foreign journalists

[edit]

- In January 2014 the Azerbaijani journalist Mahir Zeynalov was deported after being sued by the President for posting links on Twitter to articles on a corruption scandal.[2]

- In September 2015,Turkey deported three foreign journalists in Diyarbakır,who were reporting on Turkey’s Kurdish issue.Two British Vice News journalists,reporter Jake Hanrahan andphotojournalist Philip Pendlebury,were detained on 27 August andthen deported on 2 September.Mohammed Ismael Rasool,a Turkish citizen who was with the British team as a fixer,was detained,questioned andfaced further legal repercussions.They were reporting on the Turkish government’s conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).[115]

- One week later,Dutch journalist Fréderike Geerdink,who was known for being the only foreign reporter based in Diyarbakır andfocusing on Kurdish issues,was deported by Turkish authorities following her second arrest in 2015.[116] Geerdink,a freelance reporter whose contributions appeared regularly in Dikan,had written a book about the Turkish strike that resulted in the Roboski massacre of Kurds,which was published in 2014 but released in English in 2015.[117]

- Rauf Mirkadirov,Azerbaijani correspondent from Ankara for Ayna andZerkalo,was extradited to Azerbaijan without access to a lawyer.He was then charged with espionage by the Azerbaijani authorities.Mirkadirov had written accounts that were critical of both governments.[2]

Hostile public rhetoric andsmear campaigns

[edit]

Particularly since 2013,the President Erdoğan andother governmental officials have resorted to hostile public rhetoric against independent journalists andmedia outlets,which is then echoed in the pro-governmental press andTV,accusing foreign media andinterest groups of conspiring to bring down his government.[2]

- Theeconomist correspondent,Amberin Zaman,was publicly denounced as a “shameless militant” by Erdoğan at a pre-electoral rally in August 2014.Erdoğan tried to intimidate her by telling her to “know [her] place”.She was then subjected to a deluge of abuse andthreats on social media by AKP supporters in the following months.[2]

- In September 2014TheNew York Times reporter Ceylan Yeğinsu was publicly smeared anddepicted as a traitor for a photograph caption in a reportage on ISIS recruitment in Turkey.TheU.S.State Department criticized Turkey for such intimidation attempts.[2]

Arbitrary denial of access

[edit]

Turkish authorities have been reported as denying access to events andinformation to journalists for political reasons.[2]

- In December 2013,after the press had unveiled an alleged corruption scandal involving top government officials,the police department announced the closure of two press rooms in Istanbul anddeclared that journalists would not be allowed to enter police facilities unless strictly for formal press conferences.[2]

- 2014 saw a worsening of discriminatory accreditation policies.AKP meetings were off-limits for critical journalists.In case of visits abroad,foreign officials had to hold separate press conferences to allow unaccredited media correspondents.[2]

Since 2011,the AKP government has increased restrictions on freedom of speech,freedom of the press andinternet use,[42] andtelevision content,[43] as well as the right to free assembly .[44] It has also developed links with media groups,andused administrative andlegal measures (including,in one case,a billion tax fine) against critical media groups andcritical journalists: “over the last decade the AKP has built an informal,powerful,coalition of party-affiliated businessmen andmedia outlets whose livelihoods depend on the political order that Erdoğan is constructing.Those who resist do so at their own risk.”[45]

These behaviours became particularly prominent in 2013 in the context of the Turkish media coverage of the Gezi Park protests.TheBBC noted that while some outlets are aligned with the AKP or are personally close to Erdoğan,”most mainstream media outlets – such as TV news channels HaberTurk andNTV,andthe major centrist daily Milliyet – are loth to irritate the government because their owners’ business interests at times rely on government support.All of these have tended to steer clear of covering the demonstrations.”[48] Few channels provided live coverage – one that did was Halk TV.[49]

Several private media outlets were reported as engaging in self-censorship due to political pressures.The2014 local andpresidential elections exposed the extent of biased coverage by pro-government media.[2]

Thestate-run Anadolu Agency andthe Turkish Radio andTelevision Corporation (TRT) have also been criticized by media outlets andopposition parties,for acting more andmore like a mouthpiece for the ruling AKP,a stance in stark violation of their requirement as public institutions to report andserve the public in an objective way.[118]

In 2014,the TRT,the state broadcaster,as well as the state-owned Anadolu Agency,were subject to stricter controls.Even RTÜK warned TRT for disproportionate coverage of the AKP; the Supreme Board of Elections fined the public broadcaster for not reporting at all on presidential candidates other than Erdoğan,between August 6 and8.TheCouncil of Europe observers reported concern about the unfair media advantage for the incumbent ruling party.[2]

During its 12-year rule,the ruling AKP has gradually expanded its control over media.[12] Today,numerous newspapers,TV channels andinternet portals also dubbed as Yandaş Medya (“Partisan Media”) or Havuz Medyası ( ” Pool Media is continue ” ) continue their heavy pro – government propaganda .[13] Several medium groups is receive receive preferential treatment in exchange for AKP – friendly editorial policy .[14] Some of these medium organization were acquire by AKP – friendly business through questionable fund andprocess .[15]

Leaked telephone calls between high ranking AKP officials andbusinessmen indicate that government officials collected money from businessmen in order to create a “pool media” that will support AKP government at any cost.[119][120] Arbitrary tax penalties are assessed to force newspapers into bankruptcy—after which they emerge,owned by friends of the president.According to a recent investigation by Bloomberg,[121] Erdoğan is forced force a sale of the once independent dailySabah to a consortium of businessman lead by his son – in – law .[122]

Major media outlets in Turkey belong to certain group of influential businessman or holdings.In nearly all cases,these holding companies earn only a small fraction of their revenue from their media outlets,with the bulk of profits coming from other interests,such as construction,mining,finance,or energy.[123] Therefore,media groups usually practice self-censorship to protect their wider business interests.

Media not friendly to the AKP are threatened with intimidation,inspections andfines.[16] These media group owners face similar threats to their other businesses.[17] An increasing number of columnists have been fired for criticizing the AKP leadership.[18][19][20][21]

In addition to the censorship practiced by pro-government media such as Sabah,Yeni Şafak,andstar,the majority of other newspapers,such as Sözcü,Zaman,Milliyet,andRadikal have been reported as practicing self-censorship to protect their business interests andusing the market share (65% of the total newspapers sold daily in Turkey as opposed to pro-government media[124]) to avoid retaliatory action by the AKP government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[125]

During the period before the Turkish local elections of 2014,a number of phone calls between prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan andmedia executives were leaked to the internet.[126] Most of the recordings were between Erdoğan andHabertürk newspaper & TV channel executive Fatih Saraç.In those recordings,it can be heard that Erdoğan was calling Fatih Saraç when he was unhappy about a news item published in the newspaper or broadcast on TV.He was demanding Fatih Saraç to be careful next time or censor any particular topics he is not happy about.[127] At another leaked call,Erdoğan gets very upset andangry over a news published at Milliyet newspaper andreacts harshly to Erdoğan Demirören,owner of the newspaper.Later,it can be heard that Demirören is reduced to tears.[128] During a call between Erdoğan andeditor-in-chief of star daily Mustafa Karaalioğlu,Erdoğan lashes out at Karaalioğlu for allowing Mehmet Altan to continue writing such critical opinions about a speech the prime minister had delivered recently.In the second conversation,Erdoğan is heard grilling Karaalioğlu over his insistence on keeping Hidayet Şefkatli Tuksal,a female columnist in the paper despite her critical expressions about him.[129] Later,both Altan andTuksal got fired from star newspaper.Erdoğan acknowledged that he called media executives.[130]

In 2014,direct pressures from the executive andthe Presidency have led to the dismissal of media workers for their critical articles.bianet records over 339 journalists andmedia workers being laid off or forced to quit in the year – several of them due to political pressures.[2]

- In August 2014 Enis Berberoğlu,the editor-in-chief of hürriyet newspaper,quit the paper right before the 2014 Turkish presidential election.It has been reported that he was forced to resign after a clash with the publishing company Doğan Holding,due to Berberoğlu’s refusal to fire a columnist.Theday before,Erdoğan had publicly criticized the Doğan group.hürriyet denied pressures related to the case.[2]

- Theheadquarters of Nokta,an investigative magazine which has since been closed because of military pressures,were searched by police in April 2007,following the publication of articles examining alleged links between the Office of the Chief of Staff andsome NGOs,andquestioning the military’s connection to officially civilian anti-government rallies.[131][132] Themagazine also gave details on military blacklistings of journalists,as well as two plans for a military coup,by retired generals,aiming to overthrow the AKP government in 2004.[133] Nokta had also revealed military accreditations for press organs,deciding to whom the military should provide information.[134]Alper Görmüş,editor of Nokta,was charged with insult andlibel (under articles 267 and125 of the Turkish Penal Code,TPC),andfaced a possible prison sentence of over six years,for publishing the excerpts of the alleged journal of Naval Commander Örnek in the magazine’s March 29,2007 issue.[131] Nokta journalist Ahmet Şık anddefense expert journalist Lale Sarıibrahimoğlu were also indicted on May 7,2007,under Article 301 for “insulting the armed forces” in connection with an interview Şık conducted with Sarıibrahimoğlu.[131]

- Prosecution of media workers suspected to be linked with the Group of Communities in Kurdistan,alleged urban branch of the PKK,led to over 46 journalists being arrested as allegedly part of the “press wing” of the group in 2011.Most of them were released pending the trial under antiterrorism laws.Among them were the owner of Belge Publishing House,Ragıp Zarakolu,andhis son Deniz,editor at Belge.Ragıp was released in April 2012,andDeniz in March 2014,both pending trial.[2]

- TheCommittee To Protect Journalists reported that in 2012 Turkey had more journalists in custody than any other country in the world.[135]

- In 2013,the opposition in Turkey claimed that dozens of journalists had been forced from their jobs for covering antigovernment protests.[135]

- In 2014,media outlets were raided andjournalists jailed in connection with the governmental crackdown on the Gülen movement,a former ally of Erdoğan,now disgraced.On 14 December 2014 authorities searched the premises of the Zaman newspaper andarrested several media workers,including the editor in chief Ekrem Dumanlı,as well as Hidayet Karaca,general manager of the Samanyolu Media Group,andcharged them with “establishing andmanaging an armed terror organization” to reverse state power.Most journalists were released in the following days,pending trial.[2]

- In November 2015 Can Dündar,editor of the prominent secularist Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet,andErdem Gül,the newspaper’s capital correspondent in Ankara,were jailed facing life in prison.Theprosecution stemmed from an article published with the headline “Here are the weapons Erdoğan claims to not exist‟ on May 29,2015.Theimages were showing MIT (Millî İstihbarat Teşkilâtı , the Turkish National Intelligence Agency) tracks sending weapons to Syria.They were arrested for “Procuring information as to state security‟,”Political andmilitary espionage‟,”Declaring confidential information‟ and”Propagandizing a terror organization‟.[136][137][138] They were released on 26 February 2016,after the Turkish Constitutional Court ruled that their rights were violated during the pre-trial detention; the imprisonment lasted 92 days.[139] On May 6,2016,Istanbul’s 14th Court for Serious Crimes convicted both Dündar andGül for revealing state secrets that posed a threat to state security or to Turkey’s domestic or foreign interests.Dündar was sentenced to seven years in prison,reduced to five years and10 months; andGül to six years,reduced to five,under Article 329 of the Turkish Penal Code.[140][139]

- Reporters Without Borders said the arrests sent “an extremely grave signal about media freedom in Turkey.” This crackdown on the press,which has reached new levels in March 2016 with the seizure of opposition newspaper Zaman,one of Turkey’s leading media outlets,has sparked widespread criticism inside Turkey as well as internationally.TheNew York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has declared that Press freedom in Turkey is “under siege”.[141] Jodie Ginsberg,the CEO of index on censorship,a campaigning organisation for freedom of expression,has declared that “Turkey’s assault on press freedom is the act of a dictatorship,not a democracy”.[142]

- In the course of the 2016 Turkish purges,the licenses of 24 radio andtelevision channels andthe press cards of 34 journalists accused of being linked to Gülen were revoked.[143][144] Two people were arrested for praising the coup attempt andinsulting President Erdoğan on social media.[145] On 25 July,Nazlı Ilıcak was taken into custody.[146]

- On 27 July 2016,President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan shut down 16 television channels,23 radio stations,45 daily newspapers,15 magazines and29 publishing houses in another emergency decree under the newly adopted emergency legislation.Theclosed outlets notably include Gülen-affiliated Cihan News Agency,Samanyolu TV andthe previously leading newspaper Zaman ( include its English – language versiontoday ‘s Zaman),[147] but also the opposition daily newspaper Taraf which was know to be in close relation with the Gulen Movement .[47] Since Zaman’s seizure,the newspaper radically changed its editorial policy.[148]

- In late October 2016,Turkish authorities shut down 15 media outlets,including one of the world’s only women’s news agencies,anddetained the editor-in-chief of the prominent secularist Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet,”on accusations that they committed crimes on behalf of Kurdish militants anda network linked to the US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen”.[149]

Protest banners at the headquarters of raided media company Koza İpek

- On 26 October 2015,just a few days before the November 1 general elections,Koza İpek Holding was placed under a panel of mainly pro-government trustees.Thecompany’s media assets include two daily newspapers,Bugün andMillet,andtwo TV/radio stations,Bugün TV [ tr ] andKanaltürk TV.[150] İpek Media Group was close on 29 February 2016 .[151]

- On 4 March 2016,the opposition newspaper Zaman was likewise place under a panel of government – align trustee .[152] On 8 March 2016,Cihan News Agency,which was also owned by Feza Publications,placed under trustees like Zaman.[153]

- As to January 18,2017,more than 150 media outlets were closed andtheir assets liquidated by governmental decrees.[72][73][154] Under emergency decree No.687 of February 9,2017,Turkey’s Saving Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) will be authorized to sell companies seized by the state through the appointment of trustees.[155][156] Also,through the use of emergency decrees- such as Nos.668 (July 27,2016),675 (October 29,2016) and677 (November 22,2016),178 media organizations were closed down being charged of having terrorist affiliations.As to November 2016,Twenty-four of these shut-down media organizations were radio stations,twenty- eight televisions,eighty newspapers.[157]

Removing channels from government-controlled TV satellites

[edit]

Türksat is the sole communications satellite operator in Turkey.There have been allegations that TV channels critical of the AKP party andPresident Erdoğan have been removed from Türksat’s infrastructure,andthat Türksat’s executive board is dominated by pro-Erdoğan figures.

In October 2015 a video recording emerged of a 2 February 2015 conversation between Mustafa Varank,advisor to President Erdoğan andboard member of Türksat,andsome journalists in which Varank states that he had urged Türksat to drop certain TV channels because “they are airing reports that harm the government’s prestige”.Later that year the TV channels Irmak TV,Bugün TV,andKanaltürk,known for their critical stance against the government,were notified by Türksat that their contracts would not be renewed as of November 2015,andwere told to remove their platforms from Türksat’s infrastructure.[158]

Türksat dropped TV channels critical of the government from its platform in November 2015.Thebroadcasting of TV stations—including Samanyolu TV,Mehtap TV,S Haber andRadio Cihan—that are critical of the ruling AKP government were halted by Türksat because of a “legal obligation” to the order of a prosecutor’s office,based on the suspicion that the channels are supporting a terrorist organization.Among the TV andradio stations removed were Samanyolu Europe,Ebru TV,Mehtap TV,Samanyolu Haber,Irmak TV,Yumurcak TV,Dünya TV,MC TV,Samanyolu Africa,Tuna Shopping TV,Burç FM,Samanyolu Haber Radio,Mehtap Radio andRadio Cihan.[159]

Thecritical Bugün andKanaltürk TV channels,which were seized by a government-initiated move in October 2015,were also dropped from Türksat in November 2015.Later on 1 March 2016 these two seized channels closed due to financial reasons by government trustees.[160]

In March 2016 the two TV channels from other wings of the politics were also removed from Türksat,namely,Turkish Nationalist Benguturk andKurdish Nationalist IMC TV.[161]

On 25 September 2017,Turkey decided to remove broadcaster Rudaw,which is affiliated to the Kurdistan Region,from its satellite broadcasting on the same day voting took place on an independence referendum in the KRG.[162]

Censorship of sensitive topics in Turkey happens both online andoffline.Kurdish issues,the Armenian genocide,as well as subjects controversial for Islam or the Turkish state are often censored.Enforcement remains arbitrary andunpredictable.[2] Also,defamation of the Head of the State is a crime provision increasingly used for censoring critical voices in Turkey.[68]

In the 2018 Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index,Turkey is ranked in the 157th place out of 178 countries.[163] Thesituation for free expression has always been troubled in Turkey.[164][165] Thesituation dramatically deteriorated after the 2013 Gezi protests,[166] reaching its peak after the 15 July 2016 coup attempt.From that moment on,a state of emergency is in force,[167] tens of thousand of journalists,academics,public officials andintellectuals have been arrested or charged,mainly with terrorist charges,sometimes following some statement or writing of them.[163]

TheCouncil of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights’ report on freedom of expression andmedia freedom in Turkey,after his 2016 visits to Turkey,noted that the violations to freedom of expression in Turkey have created a distinct chilling effect,manifesting in self- censorship both among the remaining media andamong ordinary citizens.[67] In addition,the Commissioner wrote that the main obstacle to an improvement of the situation of freedom of expression andmedia freedom in Turkey is the lack of political will both to acknowledge andto address such problems.[67]

Reporting bans andgag orders

[edit]

In 2017,the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights noted that with regard to judicial harassment restricting freedom of expression the main issues consist in:[67]

- Backsliding in the case-law of the Turkish judiciary;

- Issues related to the independence of the judiciary andof the judicial culture;

- Defamation remains a criminal offence andcauses dangerous chilling effects,in particular defamation of the President of the Republic andof public officials;

- Harassment restricted the parliamentary debate,after the lift of the immunity of parliamentarians.Most of the opposition HD Party MPs are under investigations,if not in prison;

- Great restrictions of academic freedoms: many academics were dismissed,forced to resign,suspended or taken into police custody;

- Harassment involves all sectors of Turkish society,e.g.human rights defenders.There are frequent impositions of media bans or blackouts concerning events of clear public interest andan excessive use of detention on remand.

As to January 18,2017,more than 150 media outlets were closed andtheir assets liquidated by governmental decrees.[72][73][154] Under emergency decree No.687 of February 9,2017,Turkey’s Saving Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) will be authorized to sell companies seized by the state through the appointment of trustees.[155][156] Also,through the use of emergency decrees- such as Nos.668 (July 27,2016),675 (October 29,2016) and677 (November 22,2016),178 media organizations were closed down being charged of having terrorist affiliations.As to November 2016,Twenty-four of these shut-down media organizations were radio stations,twenty- eight televisions,eighty newspapers.[157]

In 2014,Turkish regulators issued several reporting bans on public interest issues.[2]

- In February 2014 it was forbidden to report on allegations of MİT involvement in the transfer of weapons to Syria.

- In March 2014 leak audio recording of a national security meeting at the Foreign Ministry were put under gag order .

- In May 2014 the Radio andTelevision Supreme Council (RTÜK) warned broadcasters to refrain from showing materials deemed “disrespectful to feelings of the families of victims” after the Soma mine disaster.Thecountry worst mining disaster,causing 301 deaths,remained absent from most mainstream media outlets.

- In June 2014 a reporting ban was issued concerning the kidnapping by ISIL of 49 Turkish citizens from the Turkish consulate in Mosul,Iraq.

- In November 2014 a court is issued in Ankara issue an unprecedented reporting ban on a parliamentary inquiry into corruption allegation concern four former minister .

- In September 2014the premises of the online newspapers Gri Hat andKarşı Gazete were raided andsearched by police after they had published information on the alleged corruption scandal.Thepolice demanded the removal of online information,despite only having a search warrant.[2]

In 2012,as part of the Third Reform Package,all previous bans on publications were cancelled unless renewed by court – which happened for most leftist andKurdish publications.[2]

Academics are also affected by government’s censorship.In this regard,the case of the Academics for Peace is particularly relevant:[85] on January 14,2016,27 academics were detained for interrogations after having signed a petition with more than other 1.000 people asking for peace in the south-east of the country,where there are ongoing violent clashes between the Turkish army andthe PKK.[86]

In television broadcasts,scenes displaying nudity,consumption of alcohol,smoking,drug usage,violence andimproper display of designer clothes logo,brand names of food anddrink andalso street signages of the name of establishment are commonly censored by blurring out or cut respective areas andscenes.[168] TV channels also practice self-censorship of subtitles in order to avoid heavy fines from the Radio andTelevision Supreme Council (Radyo ve Televizyon Üst Kurulu,RTÜK).For example,CNBC-e channel usually translates the word “gay” as “marginal“.[169]

State agency RTÜK continues to impose a large number of closure orders on TV andradio stations on the grounds that they have made separatist broadcasts.[38]

- In 2000,television channels were instructed that they would be suspended for a day if they aired the music video for ‘Kuşu Kalkmaz’,a single from Sultana’s debut album ‘Çerkez Kızı’.[170]

- In 2001,South Park was banned for 1 year in Turkey because God was shown as a rat.

- In August 2001,RTÜK banned the BBC World Service andthe Deutsche Welle on the grounds that their broadcasts “threatened national security.”[38] A ban on broadcasting in Kurdish was lifted with certain qualifications in 2001 and2002.[87]

- Early in 2007,the Turkish government banned a popular television series called Valley of the wolf : terror,citing the show’s violent themes.TheTV show inspired a Turkish-made movie by the same name,which included American actor Gary Busey.Busey played an American doctor who removed organs from Iraqi prisoners at the infamous Abu Ghraib prison andsold the harvested organs on the black market.Themovie was pulled from theaters in the United States after the Anti-Defamation League complained to the Turkish ambassador to the U.S.about the movie’s portrayal of Jews.[171]

- In 2013,a private television channel was fined $30,000 for insulting religious values over an episode of TheSimpsons in which God was show take order from the devil .[172]

- Özgür Gündem case (1993–2016): Özgür Gündem is a pro-Kurdish andleftist media outlet based in Istanbul.From the beginning of the ‘90’s,the newspaper has been subject to raids andlegal actions,with many journalists being arrested andeven killed.Thepaper remained closed from 1994 to 2011 due to a court order.These facts were the bases for the Özgür Gündem v.Turkey case before the ECtHR.[98] On August 16,2016,there was another raid by Turkish police inside the newspaper anda court ordered its interim closure for “continuously making propaganda for Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)” and”acting as if it is a publication of the armed terror organisation”.[173] Twenty-four Gündem’s journalists were arrested andkept in precautionary detention.Only considering July 2016,the Özgür Gündem’s website was blocked twice,first on the 1st andthen on the 26th.[174]

Censorship of works of art

[edit]

- In 1935,Turkey blocked a German film production about the Ottoman sultan Abdülhamid II,because the film would show the “sensational harem life”.[175]

- In light of rising political tension in the country,Cem Karaca was forced to flee to Germany in 1979 to avoid prosecution for his politically charged anddistinctly left leaning lyrics often calling for social justice andanti-corruption.[176] Following the 1980 military coup,a warrant for his arrest was issued.His repeated refusal to return to Turkey resulted in his citizenship being revoked on 6 January 1983.It was not until 1987 that he was pardoned andwas able to return to Turkey.[177]

Graffiti in Ankara displaying the words “Free Ezhel” in reference to the artists arrest anddetention in May 2018.

- Selda Bağcan was arrested andjailed three times following 1980 Turkish coup d’état for singing in Kurdish andthe inclusion of banned poems of Nazım Hikmet within her lyrics.[178] She was imprisoned for almost 5 months between 1981 and1984 for charges relating to her songs’ lyrics.[179]

- In June 2006,police seized a collage by British artist Michael Dickinson — which showed the then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a dog being given a rosette by President Bush — andtold him he would be prosecuted.Charles Thomson,leader of the Stuckism movement,of which Dickinson is a member,wrote to then UK Prime Minister,Tony Blair in protest.TheTimes commented: “Thecase could greatly embarrass Turkey andBritain,for it raises questions about Turkey’s human rights record as it seeks EU membership,with Tony Blair’s backing.”[180] Theprosecutor declined to present a case,until Dickinson then displayed another similar collage outside the court.He was then held for ten days[citation is needed need] andtold he would be prosecuted[181] for “insulting the Prime Minister’s dignity”.[182] In September 2008,he was acquitted,the judge ruling that “insulting elements” were “within the limits of criticism”.[183] Dickinson said,”I am lucky to be acquitted.There are still artists in Turkey facing prosecution andbeing sentenced for their opinions.”[183]

- In 2016,the director of the Dresdner Sinfoniker orchestra claimed Turkey’s delegation to the European Union demanded the European Commission withdraw 200,000 euros in funding for a concert which will use the term “genocide” in texts sung andspoken during a planned show.[184]

- In 2016,three separate concerts by Sıla due to take place in Istanbul andBursa were cancelled by the local municipalities following the artists remarks regarding the then upcoming anti-coup Yenikapı Rally,held as response to the failed coup attempt in 2016.TheIstanbul Metropolitan Municipality stated that the concerts due to take place in the Cemil Topuzlu Open-Air Theatre were cancelled as a result of Sıla’s statement referring to the Yenikapı Rally as a “show” in which she would not take part.[185]

- On 6 March 2017,Zehra Doğan was sentenced to 2 years and9 months of detention for “separatist propaganda”,following a drawing of her shared on Twitter representing the Nusaybin curfew,in the South- East of Turkey.[186]

- Before the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum which would authorise changes to the Turkish constitution to increase the power of the president,a Turkish court banned a pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) song which supported the “No” on the grounds that it contravened the constitution andfomented hatred.[187]

- TheTurkish Radio andTelevision Corporation (TRT) banned the broadcasting of 208 songs in 2018 on grounds of immorality andpromoting terrorism.Thelatter reason was linked primarily to Kurdish songs,andTRT later described “immoral” content in a tweet as containing alcohol andtobacco consumption.[188]

- In 2018,Turkey’s top media watchdog,the Radio andTelevision Supreme Council (RTÜK),reviewed the English-language lyrics of pop songs,andissued fines after concluding that they were inappropriate.RTÜK issued a 17,065 Turkish Lira fine to the music channels NR1 andDream TV due to the lyrics of “Wild Thoughts” andthe same amount of fine to Power TV due to the lyrics of “Sex,Love & Water”.[189]

- On 24 May 2018,Ezhel,was arrested on charges of encouraging drug use in relation to lyrics of his songs referencing marijuana consumption,facing up to 10 years in prison.[190] This sparked national outrage,as some attributed the arrest to Ezhel being an outspoken critic of the government.[191] He was acquitted on June 19,2018.[192]

- Burak Aydoğdu (stage name Burry Soprano) was arrested on October 1,2018,andcharged with ‘encouraging drug use’ through his hit song “Mary Jane”,andlater released pending trial.[193] He was detained again andtaken to Silivri Prison in March 2021 following a courts decision to sentence the artist to 4 years and2 months in prison.[194]

- In March 2021,four employees of the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo were indicted by the Ankara Chief Prosecutor’s Office for allegedly “insulting the president” facing 4 years and8 months in prison in relation to a cartoon that portrays president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan lifting the skirt of a woman in a veil.[195][196]

- Stand-up comedian Emre Günsal was arrested on April 11,2020,andsentenced to 3 years and5 months of prison for his stand-up performance from earlier the same month which contained jokes on prominent historic figures such as Rumi,Shams Tabrizi andAtatürk.[197]

- In May 2021,the Radio andTelevision Supreme Council (RTÜK) ordered the removal of “inappropriate content” from Spotify,primarily in reference to the range of podcasts available in Spotify’s library.RTÜK went further to threaten the platform with censorship in the event of non-compliance with the order.[198]

- Diamond Tema received death threats from individuals defending sharia law after discussing a hadith about Muhammad andAisha on a YouTube program.[199] Turkish Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç made a statement on his X account.[200] Tunç recalled that an official investigation was initiated by the Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office on charges of “openly inciting the public to hatred andhostility” due to the insulting,offensive,andprovocative expressions used in the videos he shared on social media.Tunç stated that an arrest warrant was issued for Diamond Tema due to his presence in Albania.He said “Provocative,andoffensive expressions about the religion of Islam andour beloved prophet can never be accepted”.[201][202][203][204]

Censorship of films andplays

[edit]

- Sex andthe City 2 was banned from Turkish cable television because authorities saw the representation of gay marriage as “twisted andimmoral” anddeemed dangerous to the Turkish family.[205][206]

- In 2014,the film “Yeryüzü Aşkın Yüzü Oluncaya Dek” (Until the Face of the Earth Becomes a Face of Love) was removed from the programme of the International Antalya Film Festival by festival organisers after a warning that showing the film may commit the crime of insulting Turkey’s president.[207]